Sherry sales: a (false) Renaissance?

There have been a lot of contradictory statements about the popularity of sherry lately. On the one hand numerous articles mention a Sherry Renaissance, a renewed interest in sherry with ‘booming sales’ (check out recent articles from The Guardian, Forbes or The Telegraph). On the other hand, there are sales statistics which prove the opposite direction: on a general level, sherry sales continue to fall quite dramatically.

While official sources will try to focus on the good things (popularity of new styles such as en rama sherry, publications of new books, wine awards, initiatives like International Sherry Week and the European Wine Capital, growing popularity of Jerez as the most visited wine tourism destination in Spain…), it’s probably not a bad idea to look at the problems and opportunities from a wider angle. How can there be a Renaissance and a decline at the same time?

Sherry sales statistics

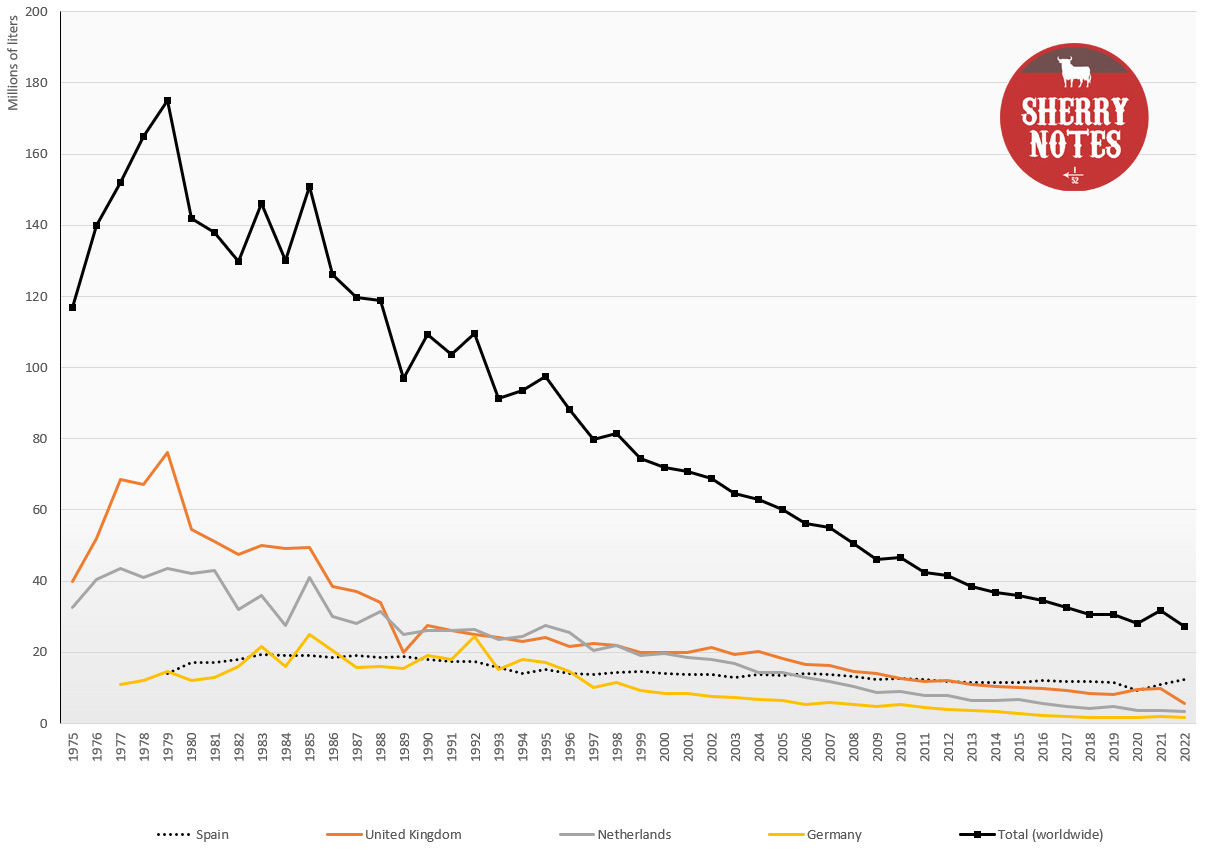

Let’s start by giving you the official sales statistics since the 1970s, as published in the annual reports of the Consejo Regulador. I’ve included the worldwide total and the four biggest markets: Spain, the UK, the Netherlands and Germany. Click the graph to see the details.

This shows a general decline from roughly 150 million liters to just over 30 million (-80%) in 30 years. The downward trend is very significant and doesn’t even slow down much. Even hopeful markets like the US and Japan (which in some recent years showed lightly increasing figures) have gone down again. Home country Spain – around 2000 the third market with just half of the UK consumption – is now the biggest market, and the only stable market as well. This doesn’t look like a Renaissance, does it?

[Graph updated to include the 2022 figures]

The downfall started in 1986 when Spain entered the European Economic Community (EEC). As a consequence the extreme subsidies of the Spanish government, which boosted exports and profitability for the bodegas, had to be halted to comply with European regulations. At the same time the competitiveness of a unified market and changing consumption habits of the public worsened a situation, going from bad to dramatic. Lowering the price was thought to be the only solution, but unfortunately in the long term this poured gasoline on the fire.

Decline of sweet sherry styles

When we do a more in-depth analysis of the sales numbers since the 1980s (I’ll spare you all the figures), it becomes clear that the sweetened blends are responsible for a large part of the decline (Medium, Cream and Pale Cream). This makes sense – they once were very popular in the UK, Netherlands and Germany, and when you look at these countries in the graph, their downward trend is more dramatic than in other countries.

Sweetened styles are related to an older audience (55+) which doesn’t think of sherry as a wine, but more as a nightcap, a Christmas tipple or something to drink in between meals, and this market segment is fading out rapidly. Because of this, the UK has now fallen below the level of Spain, after being the biggest consumer of sherry wines for decades.

However dry styles seem less affected and this is also why Spanish sales have been fairly stable during the last 15 years: they were already drinking mostly Manzanilla (as a wine for the ferias) and Fino (as the tapas wine par excellence) and they continue to do so. However this is also not entirely healthy: almost half of the yearly sherry consumption in Spain is sold during the Andalusian festivals of April, which means the figures are far less impressive throughout the rest of the year and the rest of the country.

Fino and Manzanilla are rising

In other countries the dry wines are slowly becoming more popular. It’s fair to say the sales of ‘quality sherry’ are slowly going up and the average drinker is becoming younger. The renewed audience is more interested in the story behind the product as well. As with gourmet food and other types of drinks, consumers want to know the producer, learn how they make their products, understand the differences and even visit the wonderful country where it’s made.

The slow rise of dry sherry is mainly due to Fino and Manzanilla. Palo Cortado sales are rising as well, but Amontillado and dry Oloroso are dropping even more dramatically than the sweet genres, so it’s important to recognize it’s not just a general boost of dry sherry. Note that P.X. is seeing slightly more interest as well.

A broader look: the 19th and 20th century

It’s important to know that this isn’t the first period of falling sales in the history of sherry wines.

If you look at the export statistics of the sherry industry between 1822 and 2012 (a good indication of the total sales), you’ll notice that exports were mostly under 100.000 hectolitres at the start of the 19th century, rising in the 1820s after the Peninsular Wars, leading up to around 350.000 hectolitres at the peak of what we call the sherry boom between 1860 and 1880. Many of the great sherry houses (Barbadillo, Gonzalez Byass, Williams & Humbert… were started in this period). Then there was a long and slow decline in exports, back to around 100.000 hl in 1920. This was followed by a modest revival in the 1930s, but obviously WWII meant they had to restore business again towards the 1950s.

The 20th century was a period of great successes and great depression for the sherry region. The fact that the general economy was picking up again after WWII, coupled to the fact that sherry was seen by the working class as the perfect self-rewarding drink after a hard day of work, led to an exponential surge in sales and the start of a new sherry boom in the 1950s and 1960 (much bigger than the 19th century boom).

The period between 1970 and 1985 was a golden age for sherry. However lowering popularity, Rumasa and some general issues like overproduction and lowering quality led to a significant downfall again, the downfall we’re still seeing today. Nowadays exports are back on the 19th century level, which is not a good figure if you reckon how big the global wine market has become.

A (future) Sherry Renaissance maybe?

In short: I wouldn’t call the current situation a Renaissance. Not yet. Not everywhere. And not for all sherry styles. Most of the good news is coming from specific locations in the US (major cities like New York or San Fransisco) or the United Kingdom (e.g. London which welcomed a whole list of sherry bars).

The industry is in the process of reinventing itself, with some hopeful signals, but a lot of problems still need to be handled. It is strange to see stocks are rising year after year (+17% in the past five years). It remains to be seen how this will evolve in the long run. Some say too many winemakers are still living off the income of the fame of sherry while not investing enough to provoke a new momentum for their wines.

Problems and possible solutions

Let’s list a few of the important problems and their possible solutions:

- Communication shift: sherry is a confusing category which contains many styles (and many misconceptions). We should educate people on individual styles and talk about Fino, Amontillado… each with their own merits.

- Food pairing is a key element in overcoming the prejudice towards fortified wines. There’s a big task to educate sommeliers.

- Communication channels needs to change. A lot of bodegas don’t have decent websites and aren’t active on social media. They are also relying on their distributors too much. Even the Consejo is still focusing on old media in specific countries. In this respect, sherry can learn a lot from the whisky industry for example.

- Pricing: compared to other wines of similar complexity, sherry has been too cheap. Large stocks and lowering sales equals low prices, but a fair price is necessary for consumers and for producers.

- Premiumization: related to pricing is the shift towards higher-end wines. The industry should move away from the image of a cheap supermarket wine. I think we should see more single cask releases, vintage wines, special series, en rama versions…

- Experimentation: the D.O. Jerez is one of the oldest D.O.’s in Spain and one of the most traditional. New regulations are an important step forward (and can still be taken further). Embracing white wines (Vino de Pasto) can introduce more people to sherry.

- Distribution: it’s too hard to find good sherry, even when you’re willing to pay a price. If we want to reach a new generation of wine lovers, then we might need a new generation of wine distributors as well.

Sherry bodegas are becoming healthier

Personally I think sherry sales will continue to fall for years to come. In fact, in 2019 sweet sherry (Pale Cream, Medium and Cream) was still responsible for roughly 50% of all sherry sales. If the losses are related to a whole generation of sweet sherry lovers which is literally dying out, then I personally expect a further cut. On the other hand dry sherry is really picking up in certain markets like Belgium and the US, average prices are going up and the financial situation for most bodegas is better than it was ten years ago, which is a strong point as well.

Part of the loss has also been compensated by the rapidly growing sales of seasoned sherry casks which are used by the whisky industry to give their products a certain character. In fact in 2021 around 84.000 seasoned sherry casks were sold, versus the equivalent of 64.000 casks that were sold for drinking. I don’t think the related turnover and profits are being disclosed, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the sherry cask industry had overtaken the sherry wine industry by now…

Still a difficult road ahead for sherry sales

Even with the hopeful news in some areas, and as much as I love sherry, I don’t think it will ever be the hugely popular wine it once was. The challenge is to filter out types that have gone down with their audience and try to create momentum for other unique styles. Production will come down further, bodegas will operate on a smaller scale but they will focus on authentic wines. There is certainly what I would call a media renaissance: people are talking about sherry again and praising the long-standing prestige of sherry wines (even though some articles have overly positive titles). That can’t be bad in the long term, hopefully the sales numbers can stabilize soon.

On a positive note I think sherry is a flexible wine: its wide variety of styles allows producers to focus on the types that are more popular without having to turn their business upside down. We’re experiencing a shift in consumption rather than a revival in the strict sense. Interesting times are ahead.

In 2019 I paraphrased many of these ideas in a reaction on a Wine-Searcher piece: “Sherry is dying, pass the Port”.

7 Responses to Sherry sales: a (false) Renaissance?