Ancient sherry typology: Palma, Palma Cortada, Raya…

It may surprise you that the classification of sherry wines we know today, with styles like Fino, Amontillado, Oloroso… is a fairly recent development of the 20th century. Winemaking in the sherry region goes back roughly 3000 years and it’s obvious that the styles of wines went through a gradual evolution.

In the past few years young winemakers like Willy Pérez and Ramiro Ibáñez have been looking into the past and explained how sherry wines changed over time. At the same time they are now recreating some of the lost styles while putting more focus on the vineyard, vintage characteristics and terroir that defined them. If you understand Spanish, I warmly recommend their publication Las añadas en el Marco de Jerez, which is actually a precursor to their upcoming (but every so slightly overdue) book and a major source of information for this article.

In general we can say that the Fino-Oloroso continuum simply held more styles of wine in the past. Some of the ancient styles have been wiped out with industrial winemaking techniques. Nowadays some of them are simply blended away or forced into the modern classification. In this article I will explain how the history of winemaking in the sherry region shaped the wine styles we know today and how they relates to the ancient styles of the 18th and 19th century.

Until 1778: unaged wines

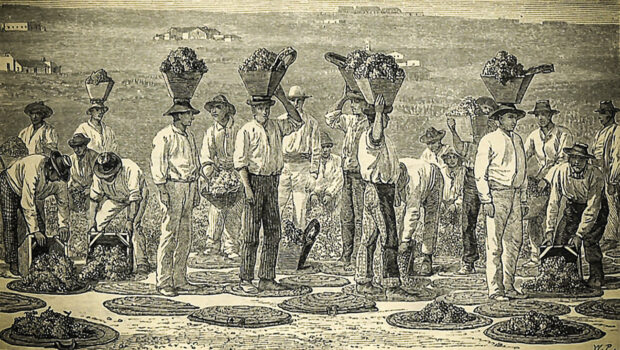

Up until the 18th century sherry production was largely based on multivarietal wines, always produced as añada wines (single vintage). In fact it was forbidden for merchants to store and age wines – only the wine of the year was available. This was dictated by powerful (local) vineyard owners who had organized themselves in the Gremio de la Vinatería. Their regulations, set in 1483, were primarily aimed at securing their yearly income by preventing (often foreign) shippers to speculate on stocks and control the price of the grapes and wines too much.

In the 18th century sherry wines are sold as unaged mostos (often exported with lees), vino añejo (of the past harvest, 1 year old) and vino reañejo (2 years). The unaged mosto was exported primarily to the UK while the older wines were consumed locally or exported to the Americas (as they are slightly more stable).

However in the 1770s a new bourgeoisie of wine merchants, led by Juan Haurie – founder of what would become Bodegas Domecq – starts legal actions against the oligarchy of vineyard owners. They manage to break it in 1778 and get a royal order which liberalizes the wine trade. The new law makes it possible to build stocks of aged wines and allows the blending of wines.

A copy of the ordinances of the ‘Gremio de la Vinateria’ from 1733

The appearance of different sherry styles

The possibility to age wines affects the sherry region significantly, acting as a catalyst for several ongoing evolutions in winemaking. For instance there is a tendency towards a higher ripeness of the grapes, aided by a short asoleo (even for the dry wines). The idea is that wines with a higher strength survive shipping to the Americas better. Oversees transport requires stable, aged wines. At the same time Palomino Fino (an early ripening grape) becomes more prominent.

Around 1800 winemakers start to understand that the selection of grape varietals (with different ripening speeds) coupled to the moment of picking are important tools to empirically steer grape juice into different styles of wines.

The classification around 1800

At the end of the 18th century this leads to the separate processing of grapes and a differentiation between pale musts (from early ripening varietals such as Palomino) and golden musts (from late ripening varietals such as Mantúo Pilas and Perruno). If you look at price lists from the 19th century, then wines are differentiated primarily by colour (pale, golden, brown) and by age. In the early 19th century this leads to a numeric system from 0-10 which indicates the age, style and price of the wine.

Records from the bodega Duff Gordon tell us that number 0 would correspond to a wine of 3 years for instance, and a n°6 would be 10 years. Higher numbers were very rare. Although the definitions could differ between bodegas, in general the numeric system was fairly widespread.

Around the same time bodegas start experimenting with vintage blends in different styles. This gradual evolution started in an attempt to cope with growing production volumes and the market demand for certain profiles of wines that weren’t always available after each harvest. Every bodega developed different recipes which contained certain amounts of older and younger wines with a respective price setting.

Rich Brown / Dry Pale / Rich Golden

For instance you could buy a ‘Rich Brown No.1’ which was darker, sweeter and cheaper, and ‘Dry Pale No.4’ which was considerably more rare and expensive. Every market had a preference towards certain styles so bodegas were creative in supplying the right blend at the best price. It is safe to say to that none of the sherry wines from this era were entirely natural: they were never produced in a straight line from grape to wine without any blending, sweetening or colouring.

This concept of large scale batches within a set of wine profiles eventually evolves into the system of criaderas and solera that is prevailing today. At first fortification and the solera system are merely seen as tools for stabilization in overseas trade but they quickly become oenological practices that shape the wines. While there are examples of soleras dating back to +/- 1770, the system was mostly consolidated in the early 19th century.

The classification of the 19th century

The sherry region experiences a golden age between 1820 and 1880, with skyrocketing sales and the foundation of many famous bodegas (Domecq in 1812, Barbadillo in 1821, González Byass in 1835, Williams & Humbert in 1877). At the same time a trend of pale sherry emerges in the 1820s. This is the time when Fino and Amontillado (which used to be local styles) are developed further and become more popular in foreign markets, while golden and brown sherries are still favoured by British consumers.

These wines presented a new challenge to winemakers: ageing wine while avoiding oxidation. The increasing production volume in the bodegas during the second half of the 19th century, as well as the popularity of pale sherry, meant the production process had to be perfected. This was only possible with an in-depth differentation in musts and a more emprirical classification of the young wines, one that lasted until the late 1900s.

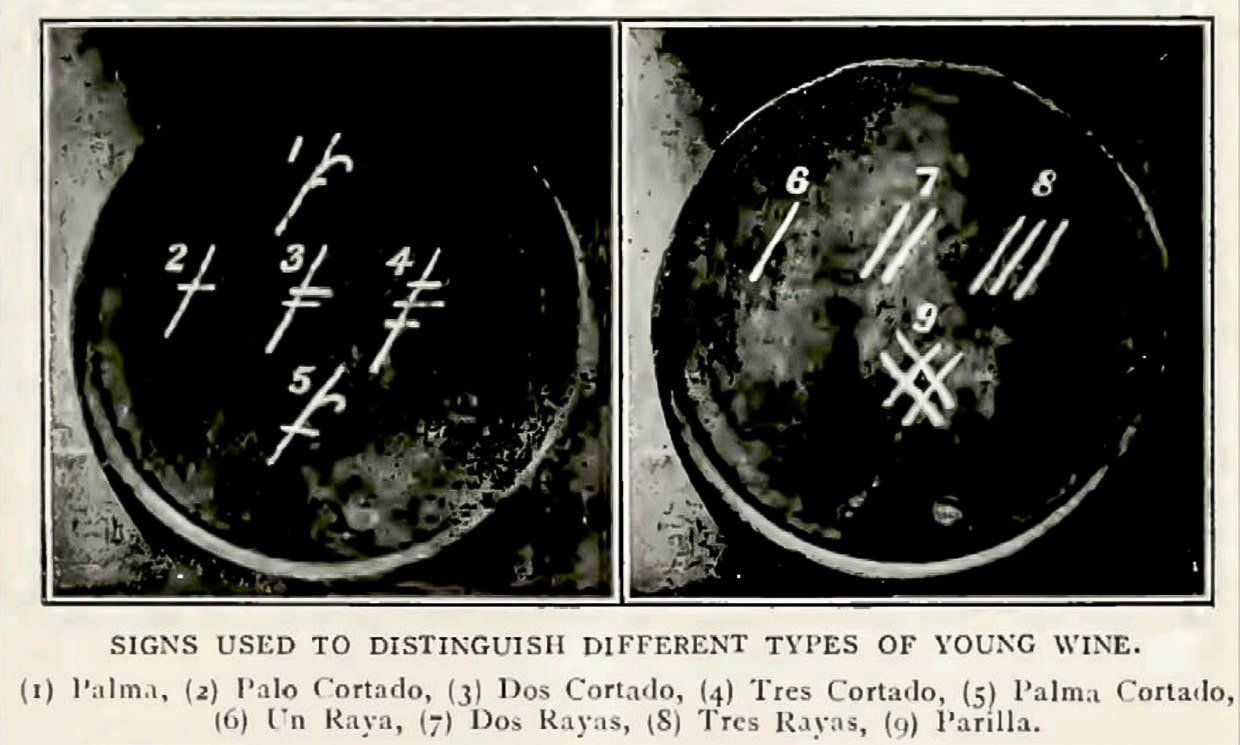

The different young wines: Palma, Palma Cortado, Palo Cortado, Raya… Based on ‘Cultivo de la vid’ by Diageo Parada y Barreto, 1868

At this point all sherry wines are classified into two major categories: palmas and rayas. Both families had a couple of subcategories. All wines were evaluated several times a year and they could shift from light (and biologically aged) to more full-bodied (and oxidatively aged).

Palma

Palmas were the vinos finos, the palest wines with a remarkable finesse and delicate character, perfectly suitable for biological ageing under flor. A wine that would be made with high quality Palomino Fino grapes picked in the first weeks of the harvest, having a slightly green profile and the lowest potential strength (15,5% at best). It was usually grape juice from a first pressing. A Palma pretty much coincides with a current-day Fino of three to four years, although at that time it would be mostly statically aged.

As the wine gets older and its character becomes more concentrated and ‘fine’, it would evolve into Dos Palmas (8-10 years), Tres Palmas (15-25 years) and Cuatro Palmas (35+ years).

For a taste of old-style Palmas, I suggest to look at the vintage Finos from Williams & Humbert or the Fino La Barajuela made by Willy Pérez. Complex wines with a lot more body and deeper aromatics than a modern Fino.

Palma Cortada

This rare wine starts as a pale Palma with almost identical characteristics, but the biological maturation is less intense. This wine would show light traces of oxidation, still in a very elegant way. If we try to describe it from a modern perspective, you could say it’s a slightly more robust Fino with a lower flor influence, or a very fine Palo Cortado with more flor influence (a modern Palo Cortado is rarely influenced by flor).

In warmer vintages even the greener grapes would have a higher potential alcohol and would shift towards Palma Cortada. After three or four years of (static) ageing a Palma Cortada would have been considered ready, but they were also well suited to age into mature Fino-Amontillado or Amontillado wines.

Luis Pérez brought back this style in his Palma Cortada 2017 ‘La Barajuela’, a wine that was produced in a similar way as his Fino Barajuela. Yet 2017 was a warm year and concentration in the grapes was extremely high. After five vintages of Fino Barajuela, the 2017 harvest ‘gave’ him a Palma Cortada. It is a wine with traces of Fino but also certain fruity notes due to the higher ripeness, and a subtle oxidative edge.

Palo Cortado

This is also considered a type of Palma as it has a similarly light and elegant initial character. They had a more golden colour though and a clear tendency towards oxidative ageing, with little or no flor development. We’ve already looked into the reasons for this deviational style in our article on Palo Cortado. The most common elements were pre-Phylloxera late-ripening grapes (other than Palomino Fino) and a slight overripe grape character due to later picking.

The overripe character is further developed by asoleo, the sunning of the grapes which was a fairly standard practice until the 20th century, even for dry wines. The natural alcohol content was above 15,5%, beyond the margins suitable for flor. Often these grapes had such a high sugar level that there would also be some residual sugar in the wine as well.

In the 19th century there was no temperature control and winemaking was slower and less automated, so it’s safe to say that the Palo Cortado style was once the prevailing style within the Palma category. In a way they were ‘near-misses’. Making a true Palma or Palma Cortada without any oxidation requires accurate monitoring of many parameters.

Palo Cortado wines were also differentiated into Dos Cortados, Tres Cortados and so on, depending on their age and concentration.

Cortado La Barajuela 2017 from Luis Pérez is salty with roasted nuts and a very fine, ripe fruit finish. It’s fresh and drinkable and you don’t note the 16.5% alcohol. A similar profile can be found in Ramiro Ibáñez’ Agostado / Encrucijado wines.

Sherry bottles from the 1950s, mentioning some of the lost styles of sherry like Palma and Raya

Raya

Rayas had more colour from the start, as they were often made from subsequent pressings. They had more body with a more exuberant nose and a richer but also slightly harsh profile on the palate, often with a bitter edge. Their alcohol volume exceeded 15,5% so there was no flor development at all. The character of a raya was highly influenced by the inclusion of all sorts of grape varietals (other than Palomino Fino) and later ripening. Rayas were mostly produced from secondary soils, leading to a more prominent fruity character and often some volatile acidity.

A wine named una raya was still a nicely flavoured, dry and clean wine, but showing no prominent qualities. Further down the line there were inferior categories of rayas, decreasing in quality: Raya y punto (with less density), Dos Rayas (definitely from second pressing mosto, with slight defects on the nose, still suitable in a blend) and Tres Rayas (usually from the last pressings, too acidic, thin or with a nasty smell). There was also Parilla (a kind of skewed hashtag sign), which included defective wines that were used to make vinegar or distilled alcohol.

Luis Pérez made La Barajuela Raya. It combines ‘late harvest’ aromatics – something you’ll never find in modern sherry wines – with unusual acetic and cidery notes and hints of oxidation. Unique wines, quite challenging at first, but very interesting.

With long ageing, rayas could still develop into nicely aromatic Olorosos. I’ve read that a Pata de Gallina Oloroso often also originated from raya wines, as they generally contain more glycerol.

An old sign in the former Sandeman pressing house, now owned by Bodegas Luis Pérez

Añada sherry types + Solera sherry types

By the mid 19th century, añada wines are still at the base of sherry production. On the other hand stocks of ‘aged blends’ with set profiles evolve into the dynamic systems of fractional blending as we known it today – first for the oxidatively aged wines which were easier to control, later also for biological ageing. The switch to ‘composed’ wines that were regularly topped up also led to new categories and names.

Legendary winemakers like Manuel Barbadillo, Manuel María González (of González Byass) and Juan Pedro Domecq slowly formed the modern classification as we know it today. Tio Pepe became one of the first modern Finos (together with San Patricio) while Domecq set the guidelines for the big categories of oxidative wines.

Slowly a typology for solera wines emerges. Palmas were used to feed soleras of Fino sherry. However the idea of a modern Fino de solera didn’t appear until the 1870s. Añada wines previously called Palo Cortado would be used to feed soleras of an emerging typology called Oloroso sherry. The rayas were at the base of a dynamic wine that was named Jerezano style, basically a slightly courser type of Oloroso.

Towards the modern types of sherry

Pricelists from around 1850 show a mix of various names, from the old classification and what we know today. It wasn’t uncommon to see a Dos Cortados or a Palma in the same list as a Fino, Oloroso and Amontillado. The former were añada wines, the latter were solera-based. A series of elements will ultimately steer away from the old classification:

- the Phylloxera plague (which makes all sherry types monovarietal)

- a better understanding of biological ageing (thanks to Pasteur and others)

- and the sherry crisis from the 1870s to the early 1920s (caused by lowering quality, rumous about the unhealthy nature of sherry and a problem of imitation wines).

These evolutions lead to an even wider acceptance of the solera system and a higher standardization.

The modern sherry typology: Fino vs Oloroso

From the early 1900s a new typology emerge, gradually replacing the old classification. The typology that still prevails today was consolidated in the 1920s and the cornerstone of the foundation of the D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry. It is based on two opposing styles: Fino and Oloroso. By then all of these wines are matured exclusively in soleras.

The better knowledge of how to produce Fino (Palma) wines without any oxidation leads to the disappearance of the Palma Cortada style. Aged Finos (previously Dos Palmas / Tres Palmas…) are named Amontillado. The Oloroso typology now becomes a wide denominator for all the oxidative styles. It includes Palos Cortado (similar to a Palma Cortada, to a certain extent), Oloroso (the former Cortados) and Raya (which are now simply thought of as a rough Oloroso with limited aromatic qualities, similar to the old Jerezano). Rayas are still used in blends, but they will disappear in the 1960s as winemaking standards improve.

The fact that certain typologies changed over the centuries, and names of añada typologies are used again for new solera-based wines (especially Palo Cortado) doesn’t help to understand the different classifications from the 19th and 20th century. Sherry wines have a complex hierarchy already, and if you add in a historic perspective, then you really need to pay attention to keep them apart.

The future of sherry?

Who knows what the future will bring? In a way we’re seeing tendencies that revert the changes of the 20th century. Every major bodega is producing vintage Fino or vintage Oloroso again. The Consejo Regulador has just accepted ‘new’ grape varieties that were common in the 19th century. Young winemarkers are reproducing the lost styles that were wiped out by industrialisation. We’re going back to the future, so to speak. Rest assured, interesting times are ahead for the sherry region, and having a better understanding of the past will certainly help.